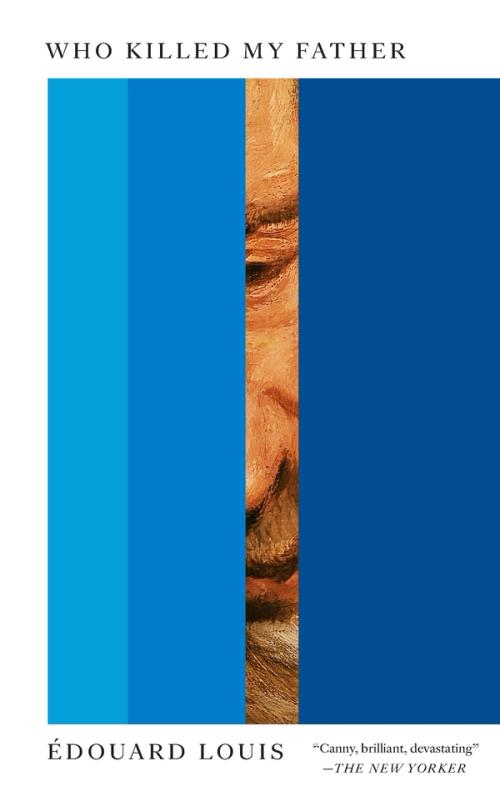

Who Killed My Father

Literature by Édouard Louis

This bracing new nonfiction book by the young superstar Édouard Louis is both a searing j’accuse of the viciously entrenched French class system and a wrenchingly tender love letter to his father.

Who Killed My Father rips into France’s long neglect of the working class and its overt contempt for the poor, accusing the complacent French—at the minimum—of negligent homicide.

The author goes to visit the ugly gray town of his childhood to see his dying father, barely fifty years old, who can hardly walk or breathe:

“You belong to the category of humans whom politics consigns to an early death.” It’s as simple as that.

But hand in hand with searing, specific denunciations are tender passages of a love between father and son, once damaged by shame, poverty and homophobia. Yet tenderness reconciles them, even as the state is killing off his father. Louis goes after the French system with bare knuckles but turns to his long-alienated father with open arms: this passionate combination makes Who Killed My Father a heartbreaking book.

Translated from the French by Lorin Stein

Paperback(published May, 02 2023)

- ISBN

- 9780811235044

- Price US

- 12.95

- Trim Size

- 4.5x7.25

- Page Count

- 96

Clothbound(published Mar, 26 2019)

- ISBN

- 9780811228503

- Price US

- 15.95

- Trim Size

- 5x8

- Page Count

- 96

Ebook

- ISBN

- 9780811228510