As author

Herscht 07769

The World Goes On

A Mountain to the North, a Lake to the South, Paths to the West, a River to the East

Spadework for a Palace

Chasing Homer

Baron Wenckheim's Homecoming

The World Goes On

The Last Wolf & Herman

Seiobo There Below

Satantango

Animalinside

War & War

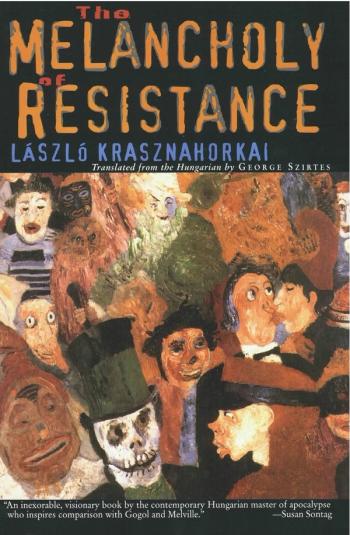

The Melancholy of Resistance

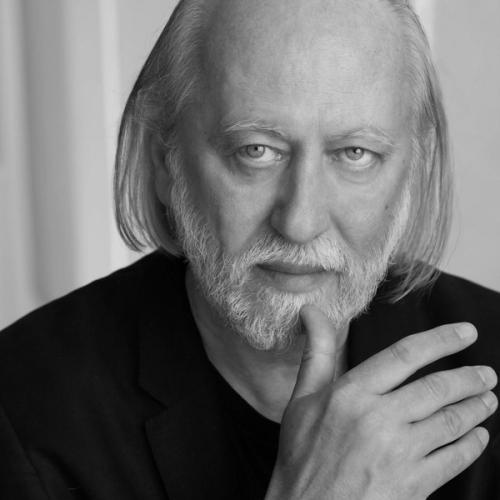

László Krasznahorkai

László Krasznahorkai was born in Gyula, Hungary, in 1954. He worked for some years as an editor until 1984, when he became a freelance writer. He now lives in reclusiveness in the hills of Szentlászló. He has written five novels and won numerous prizes, including the 2019 National Book Award for Translated Literature, the 2015 Man Booker International Prize, and the 2013 Best Translated Book Award in Fiction for Satantango. In 1993, he won the Best Book of the Year Award in Germany for The Melancholy of Resistance. For more about Krasznahorkai, visit his extensive website.